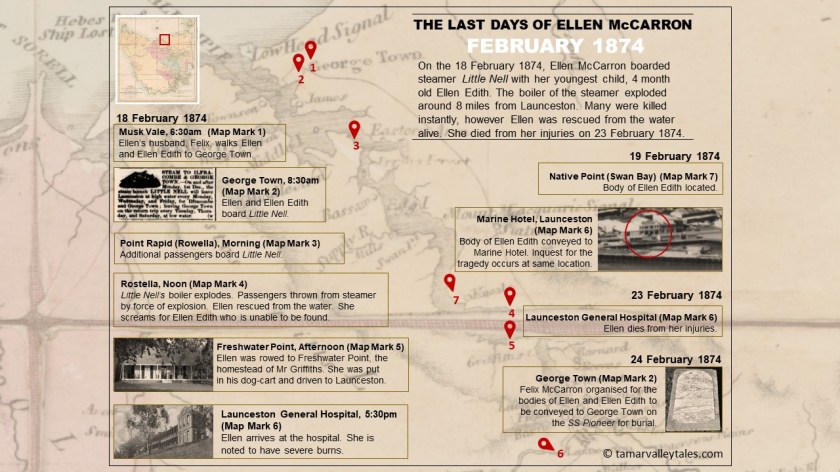

The weather forecast for Wednesday, February 18, 1874, promised a fine summer’s day. The steamer, Little Nell, left George Town, a thrice-weekly routine. However, the journey on that particular day turned out to be catastrophic.

Introduction to Little Nell

It was the summer of 1874, and the day was shaping up to be clear. Docked at the jetty was Little Nell, ready to set sail from George Town to Launceston. Nell was a small steamer, formerly known as Resolute when she worked in Hobart. Now, it served as a passenger ferry, shuttling travellers along the Tamar River six days a week – departing from George Town to Launceston three day a week, and the reverse trip on the other three. The fare was 7 shillings and sixpence, equivalent to about $48 today.

The three-person crew welcomed five passengers, including my ancestor, Ellen McCarron, and her youngest daughter, Ellen Edith, who was still a baby.

The McCarron Family

Ellen McCarron was the daughter of John and Ellen Jones (nee Cochlin). Her father, John, served as the storekeeper of the Iron Store in George Town.

Ellen’s life remained largely unknown until her marriage to Felix McCarron. At the young age of 15, Ellen became a bride on Boxing Day in 1863 at St Mary Magdalene in George Town. An older sister of Ellen had run away when her request to marry at 15 was declined by their parents, possibly influencing their support for Ellen marrying at a young age.

Ellen and Felix welcomed five children during their marriage: Catherine, Felix, William, Amy, Fred, and Ellen Edith, all born between 1864 and 1873. The family settled at ‘Musk Vale,’ a property located four miles from George Town along the Piper’s River road.

The Fateful Journey to Launceston

For Ellen and baby Ellen Edith, the day began early, with Felix accompanying his wife and infant from home to the steamer at half-past six in the morning. He then returned to work four miles away. It’s not known why Ellen chose to take the steamer that day. She might have been traveling to Launceston for shopping or visiting her sister, Esther Begent, who lived there.

When Little Nell departed later that morning, there were eight people on board. The three crew and five passengers were joined by another three passengers along the way.

| Name | Place Embarked | Comments |

| William Gardiner (Crew) | George Town | Captain |

| Thomas McCann (Crew) | George Town | Engineer |

| William Ruttley (Crew) | George Town | Ship’s Boy |

| John Russell | George Town | Manager of Excelsior Gold Mine |

| Thomas Hickson | George Towb | Partners with Messrs Godwin and Sandberg, of a rich minig claim at 9 Mile Spring |

| Mr Walbourne | George Town | Proprieter of the Black Boy |

| Ellen McCarron | George Town | Boarded with her youngest child, 4 month old Ellen Edith |

| Mary Ann Welsh | Point Rapid | 16 years old. Was on her way home after staying with her aunt at East Arm |

| William McDonald | Sidmouth | Storekeeper |

| George Kerrison | Gravelly Beach | Farmer |

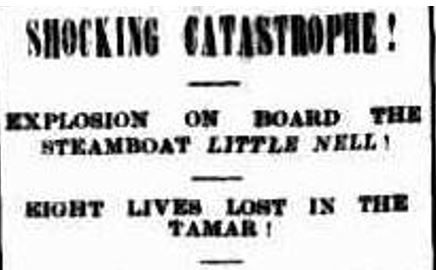

Little Nell’s journey was uneventful until approximately ten minutes past noon when the steamer approached Rostella, a homestead eight miles from Launceston. The tug-boat Tamar was nearby, closing in on Nell until eventually overtaking her. While some later suggested Nell and Tamar had been racing, this was rejected by some witnesses who stated that Nell maintained a steady pace.

Moments later, Nell’s piston rod failed, causing the steamer to come to a halt and initiating a tragic series of events. The engineer, distracted while trying to repair the piston, failed to release the safety valve to alleviate pressure. He opened the door to stoke the coal fire, resulting in an immediate and catastrophic explosion. Witnesses described the horrific sight of bodies thrown into the air by the sheer force of the blast.

Mr. Gilder and his son, James, were sailing their cutter, Margaret, ahead of Nell and Tamar. Upon witnessing the explosion, James rowed to the scene in the cutter’s dinghy. He managed to rescue Ellen, who was screaming for her baby, and a man named McDonald. Unfortunately, James was unable to reach two other people before they sank. He then rowed to Thomas Hickson, who was holding onto debris to stay afloat. By this time, his father had joined him in the dinghy and helped pull Hickson aboard. McDonald, who had severe injuries, was transferred to Margaret to be taken to Launceston.

James rowed Ellen to Freshwater Point, Mr. Griffiths’ property. With severe burns to her arms, legs, back, and face, Ellen required medical attention. She was placed in Mr. Griffith’s dog-cart, where she was made as comfortable as possible. Mr. Walker of Rostella, who had witnessed the explosion, drove Ellen to the Launceston General Hospital, taking care not to exacerbate her pain.

The Launceston General Hospital, newly built and opened in 1863, was admired for its spaciousness and cleanliness. Ellen arrived there around half-past five in the evening and was seen immediately by Dr. McQueen. The likely treatment she received involved cooling the burns with ice or immersion in cold water.

Over the following days, efforts were made to recover some of the bodies from the Tamar River, including that of baby Ellen Edith. The damaged remains of Little Nell were towed to Haly’s dock.

Despite an initial rally, Ellen’s condition deteriorated. Ellen’s extensive and severe burns contributed to her death on February 23, 1874. Her husband, Felix, made arrangements to convey both Ellen and Ellen Edith’s bodies to George Town for burial.

The Inquest

In March 1874, an inquest was conducted at the Marine Hotel in Launceston. Mr. Edwards, part-owner of Nell and her former engineer in Hobart Town, testified that he had never allowed steam pressure to exceed 80 pounds. However, he had heard that since Nell’s relocation to the Tamar, she routinely operated with 110 pounds of steam pressure. It was suggested that when the steamer stopped for 5 minutes due to the broken piston, an additional 20 pounds of steam would have built up, ultimately reaching 130 pounds, which was deemed sufficient to cause the explosion.

Survivor Thomas Hickson provided his account at the inquest, explaining that Nell had been traveling at a steady pace, with the tug Tamar overtaking her. When Nell came to a stop, Hickson went to the boiler room, where the engineer explained that the piston rod had failed. The engineer did not release the steam pressure before opening the door to the coal fire, triggering the explosion.

Witnesses provided vivid accounts of the explosion and the discovery of the deceased. In a distressed state, Felix McCarron gave evidence of his wife’s final days.

After half an hour of deliberation, the jury delivered their verdict, attributing the accident and subsequent fatalities to the boiler’s rupture due to overpressure. The jury did not comment on the cause of the overpressure but recommended the establishment of government oversight for all steam boilers in the colony and that all individuals in charge of engines should be qualified and licensed.

Conclusion

Within days of the tragedy, Nell became a local attraction. Many expressed surprise at the complete destruction, with only her shell remaining. Despite this, Nell was not abandoned or scrapped. She underwent repairs and started a new life as a sailing ketch named Rescue.

Nell enjoyed a period of trade on Tasmania’s North-West Coast, transporting cargo such as potatoes. Unfortunately, during one such trip, Nell was lost at sea off Circular Head, bringing her story to an end.

In the George Town cemetery, there lies a shared headstone for Felix and Ellen. Felix remarried and had more children but was reunited with his first love in death.

More from Tasmania’s Past

Interested in reading another story from a woman in Tasmania’s past? You may enjoy:

Sources

Alexander, Alison (2006), Gender, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/G/Gender.htm.

Birth Records, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Branagan, JG, George Town: History of the Town and District, Launceston, Regal Publications, 1980.

Colonial Times (Tasmania).

Cornwall Advertiser (Launceston).

Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston).

Courier (Hobart).

Death Records, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Hussain, H. and Choukairi, F., ‘To cool or not to cool: Evolution of the treatment of burns in the 18th century’, International Journal of Surgery, Vol. 11, pp. 503-506)

Inquest Records, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Launceston Examiner.

Lee, K.C., Joory, K. and Moiemen, N.S., ‘History of burns: The past, present and future’ Burns & Trauma Vol. 2, Issue 4, pp. 169-180.

Marriage Records, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Measuring Worth, ‘Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1270 to Present’, www.measuringworth.com/ppoweruk.

Mercury (Hobart).

National Library of Australia, ‘How Can I Calculate the Cost of Old Money’, https://www.nla.gov.au/faq/how-can-i-calculate-the-current-value-of-old-money.

McDonald, P.F., Age at First Marriage and Proportions Marrying in Australia 1860-1971 (Thesis), Australian National University, 1972, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/117075 .

Phillips, Dianne, An Eligible Situation: The Early History of George Town and Low Head, Canberra, Karuda Press, 2004.

Tasmanian.

Leave a comment