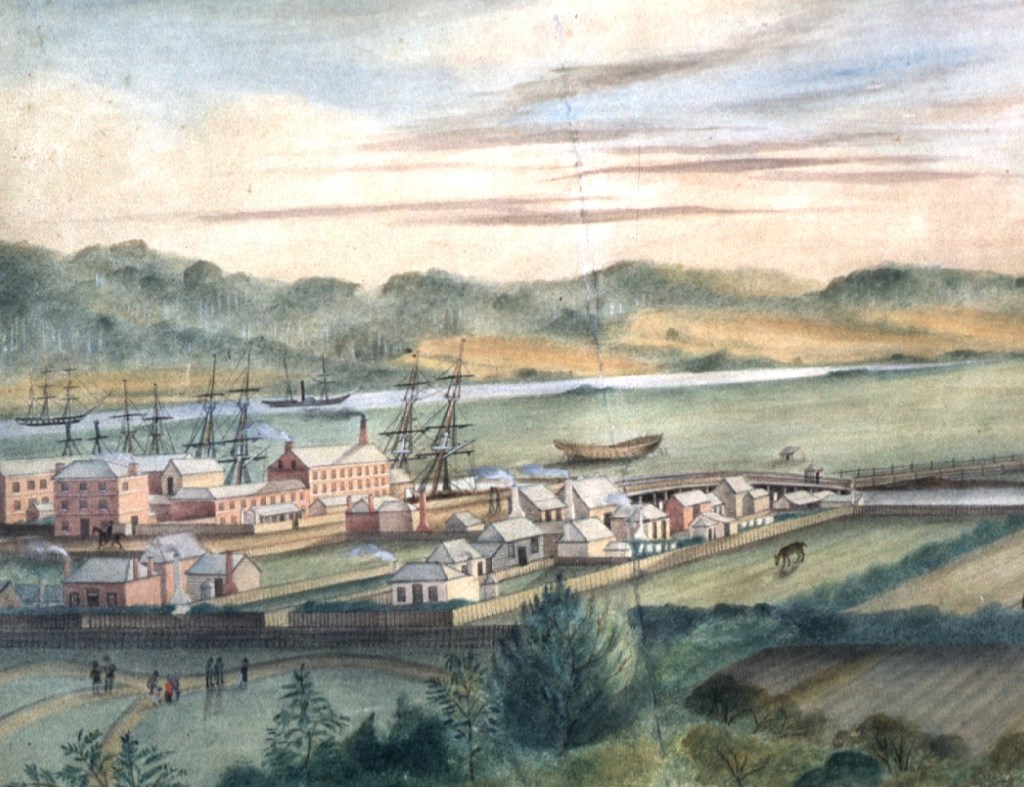

Feature Image: Launceston Tamar Bridge, Sarah Fogg, State Library of Tasmania

It was no ordinary day of work for Henry Robinson, pilot and harbour-master, who stepped on board the brig Active in October 1811. Before him was a tall, richly-clad officer reclined on an Indian settee, with the ship’s officers standing at a respectful distance.

Robinson was curious and asked about the distinguished gentleman. He was told that it was the royal General, Count McHugo, an Indian officer of the highest class. As the brig navigated down the Tamar River, Robinson wasted no time signalling the arrival of a person of distinction who would soon disembark in Launceston. “This will be a big day in the history of Launceston”, he said.

Described as prepossessing, well-informed and intelligent, Count McHugo stood over six feet tall, casting a striking figure on his arrival. He was generous to the struggling infant colony, distributing goods from his cargo and extending credit wherever asked.

A Regal Presence in Launceston

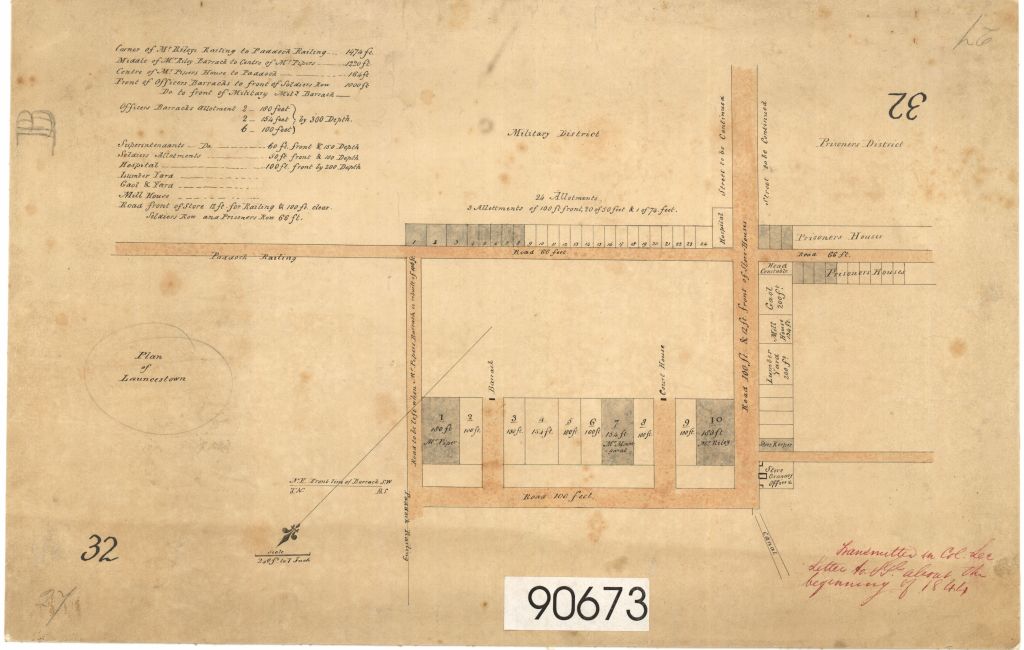

A military man himself, McHugo took a keen interest in the welfare of the infantry stationed in Launceston, giving gifts of Madeira wine and lending a sympathetic ear to their complaints. Incensed by their conditions, McHugo took matters into his own hands, marching down the streets to Commander Gordon and demanded an official inquiry into the soldiers’ living conditions.

He was, he told Gordon, a Prince of the Blood who had travelled South to see how the government was faring. He demanded the reins of government be returned to the Crown, represented by his royal self. Gordon was said to be suffering sun-stroke at the time and wasn’t himself, and he quickly yielded.

McHugo’s first royal decree was to have Gordon charged and arrested for all the troubles the struggling town was experiencing. He took depositions from the military and at the conclusion of his inquiry, he found Gordon negligent in his administration of the colony and sentenced him to hang. Gordon’s subordinates pleaded for clemency for him but were told to obey or to join Gordon. They decided to keep the peace. There were murmurings within the town by now, though. McHugo retaliated by locking up the entire civilian population to await execution.

The Fall of Count McHugo

In fortunate timing, Lieutenant Lyttleton returned to Launceston from holidaying in the Norfolk Plains (Longford) area. He saw the situation clearly for what it was. He intervened, rescuing Gordon from his cell and arresting McHugo himself, effectively ending his reign.

McHugo was marched to the Active, where he was tied to his cot to prevent him from injuring others, and the brig sailed for Sydney.

New South Wales Governor Lachlan Macquarie was furious.

Gordon actually surrendered his command to Mr. McHugo, who was likely to have made a very alarming use of the power so yielded to him had not junior officers intervened.

Lachlan Macquarie, Col Sec Correspondence 1812

McHugo’s actions exposed vulnerabilities in the fledgling antipodean colonies. How was it that a stranger, albeit articulate and distinguished, could so quickly assume control without any qualification or authority to do so. Macquarie must have worried about how easily this situation arose and how quickly control of the colony could have been lost.

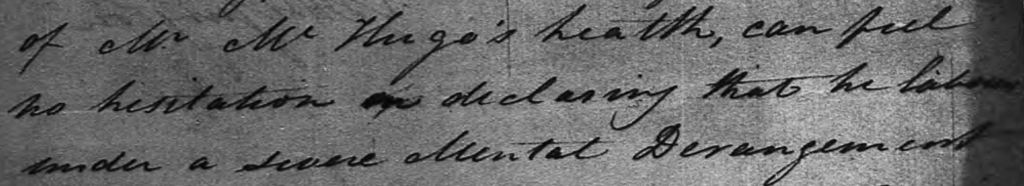

McHugo’s Mental Health Struggles

McHugo was handed over to Vice-Regal Surgeon William Redfern, who diagnosed him as being “in a state of outrageous insanity” and of being completely incapable of managing his own affairs. Deported back to India, McHugo was confined to an asylum, where he reflected bitterly on his treatment and continued to nurse his delusions of royal lineage.

During this period, Macquarie wound up McHugo’s affairs, with the Active’s cargo disposed of and the money sent to McHugo’s agent in Calcutta. Macquarie ensured thorough documentation of the situation, including of the disposal of property.

Meanwhile, in Launceston, Major Gordon was relieved of his duties and Lieutenant Lyttleton was proclaimed a hero. Repercussions from McHugo’s reign continued, however, when his trustees in India demanded payment for the goods McHugo had lavishly bestowed on credit. Peter Mills and George Williams, who had been gainfully employed, were unable to pay their creditors and turned to bushranging.

McHugo’s Life Beyond Van Diemen’s Land

As McHugo languished in confinement, his claims to royal linage persisted. He returned to England following his release from the Calcutta asylum in 1815 and pleaded to the highest echelons for recognition of his claim to the throne. He declared the Prince Regent George IV an illustrious usurper. His pleas, of course, went unheeded.

McHugo also wrote to Colonial Secretary, Lord Bathurst, seeking restitution for cruelties toward him in New South Wales. Macquarie’s detailed documentation, provided clear evidence of McHugo’s mental state and of the liquidation of his assets.

Conclusion

McHugo’s brief yet tumultuous reign in Van Diemen’s Land left a lasting impact on the small colony. However, tracing McHugo’s life beyond his return to England proves challenging. Some accounts suggest he died a pauper in London, a stark contrast to the wealth and influence he wielded in Launceston. McHugo’s mental health undoubtedly played a role in his decline. Reflecting on his story raises questions about the potential outcomes had he received the support available today.

Sources

‘A Rogue Who Nearly Hanged a Lieut.-Governor’, Examiner, 6 April 1935, p.4

‘Australiana’, World’s News, 11 December 1948, p.21

‘Chapters in the Strange Story of Tasmania’, Voice, 6 June 1931, p.3

Colonial Secretary Papers relating to McHugo, 1812

‘Early Days in Tasmania’, Critic, 13 October 1916, p.3

James Dunk (2018) The liability of madness and the commission of lunacy in New South Wales, 1805–12, History Australia, 15:1, 130-150, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2017.1413942

‘Letters to the Editor’, Examiner, 4 October 1945, p.4

‘Paleological Sketch of Tasmania’, Mercury, 29 October 1874, p.2

‘The Bad Old Days: Lunatic in Power’, World’s News, 9 June 1951, p. 13

‘What Two Bad Men Can Do: The “Count” Who Captured Launceston’, Western Argus, 19 August 1930, p.36

‘Whole Population Went to Gaol When ‘King of Launceston’ Ruled, Daily Mirror, 25 September 1951, p.13

Leave a comment