My Nan used to tell me about the air-raid drills at her school in Hobart during the war. She was only a child then, small enough that the trenches at the bottom of the schoolyard seemed deep and enormous to her. When the bell rang, the children were marched out in lines and told to climb down into the earth. My Nan was matter of fact in her memories. Perhaps the war didn’t feel close to a small girl in Hobart.

The Home-Front in Tasmania

Until Darwin was bombed on 19 February 1942, most Tasmanians assumed the island’s remoteness kept it safe. Within days of the attack, the Commonwealth ordered every state to activate its dormant Air Raid Precautions plans. Civil defence committees were formed in Hobart, Launceston and the coastal towns almost overnight.

In those years, the Government of Tasmania’s Civil Defence Legion distributed printed instructions across the state, advising families what to do if the air-raid sirens sounded. People were told to keep calm, black out their windows, and take shelter “under the stairs, the table, the bed, or in the trench you have dug in your yard”.

Nan never mentioned seeing one of those posters, but she remember the drills. The sound of the bell, being told by the teachers to stop mucking about and they climbed into the trenches at the bottom of the yard.

Householders covered their panes with brown paper and shopkeepers dimmed their lights. Air-raid sirens were tested regularly and volunteer wardens patrolled the streets enforcing blackout rules. Lookout stations were established around key harbours and headlands, including the Derwent and Bass Strait approaches.

By mid-1942, Tasmania had a fully organised Civil Defence Council with volunteer rescue units, medical posts, and fire watch patrols. No bombs ever fell, but for the first time the war wasn’t something happening elsewhere it was something Tasmania was actively preparing for.

Nan’s War

Nan felt the way the war changed her daily life. There was rationing, for a start. Chocolate and chewing gum were rare treasures, spoken about with the same longing children now reserve for holidays or pets. Most treats were sent to the soldiers, and Nan remembered this not as an act of patriotism, but as childhood deprivation.

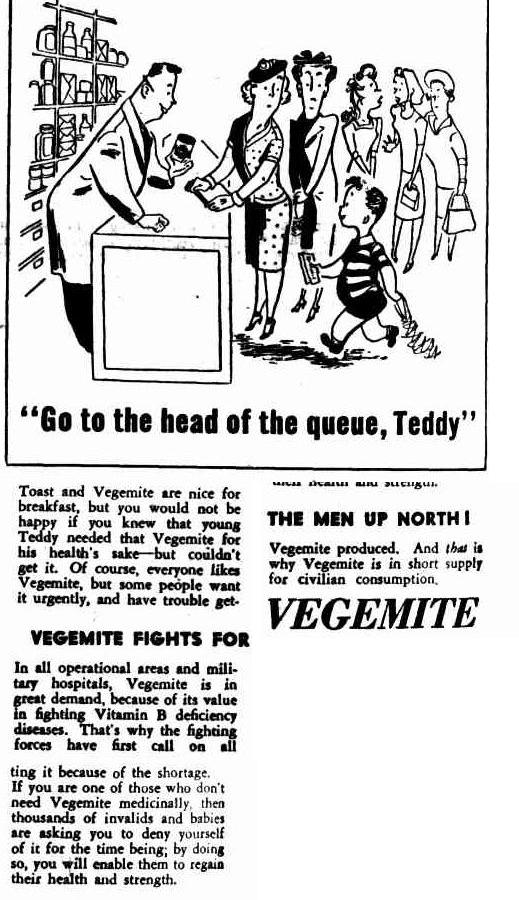

What she spoke about most often, though, was Vegemite. “We couldn’t get Vegemite,” she would say, still bitter decades later. Her older sister was sickly, and the family was allowed one small jar a month on medical grounds. Nan would sometimes get a tiny scrape from that jar, just enough to taste salt and comfort on her tongue. Even as an adult, she remembered the yearning more than the taste.

Tasmania felt a long way from the war, yet it seeped into daily life through those small losses and the quiet instructions children were expected to follow without question. Nan knew the drills were in case of enemy planes but the unspoken part was that no one believed danger would reach this far south. To the children, the enemy existed somewhere “up there,” beyond Bass Strait.

Nan never felt afraid. For her, the war was drills, chalk dust, and ration books, not danger. The children carried on with playtime and scraped knees. In her world, fear never reached her schoolyard.

What Nan didn’t know was how close the war really came, and how tightly that truth was held from the public.

Because in 1942, a Japanese submarine sank a ship in Bass Strait.

And no one told them.

The War Closer Than They Knew

The merchant vessel Iron Crown was built in 1922 and was servicing Australian trade routes when war broke out. On 4 June 1942, while sailing within Bass Strait, waters many Tasmanians assumed remote and safe, the ship was struck by a torpedo launched by the Japanese submarine I-27. The blast came suddenly. The ship sank in minutes and 38 of the 43 crew members lost their lives.

Discovery of the SS Iron Crown

The wreck was discovered in April 2019 by a CSIRO research team aboard the Investigator. The wreck was sitting upright and largely intact, 100km off Victoria’s east coast. The find confirmed historical records of the ship’s final position.

Source: [CSIRO Marine National Facility]

The Japanese submarine campaign of 1942 reached deeper into Australian waters than most Tasmanians knew. In the space of a few months, enemy submarines shelled Sydney Harbour, torpedoed ships off the New South Wales Coast, and then struck in Bass Strait. The I-27 that sank the Iron Crown was part of that same offensive, one that briefly made the southern coast a frontline.

In wartime Australia, secrecy was part of the defence. Newspapers printed vague reports, “enemy action in southern waters”, with no names, dates or casualties. Even surviving crew were cautioned against speaking publicly. The Federal government and allied departments knew that public panic could hamper morale and operations. Of all the losses that Tasmania and the nation witnessed, the sinking of Iron Crown in the narrow, supposedly secure waters of Bass Strait was kept largely out of public view.

Many Tasmanians would not learn of the event until decades later when archival records were declassified, wreck surveys conducted, and maritime historians pieced together the story.

Axis minelaying operations had touched Australia’s southern waters too with both German and Japanese forces laying mines along the east coast of Australia. But that’s a story for another time.

The War We Didn’t See

The result was that schoolchildren in Hobart practised climbing into trenches while a ship was torpedoed less than a day’s sail away. Children’s drills, rationed jars of Vegemite, silent adults.

Nan never learned to be afraid of war. It remained something that happened elsewhere, to other people. Perhaps that was the quiet success of those who kept the secret; that for one small girl in Hobart, even the nearest loss felt comfortably distant.

Years later, Nan still spread Vegemite thickly on her toast every morning, enjoying the small treat that had once been rationed and out of her reach. A small act of remembrance from a long ago time.

What We Know

- SS Iron Crown (100m ore carrier) was an Australian merchant ship built in 1922.

- It was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-27 on 4 June 1942 in Bass Strait, around 44 nautical miles SSW of Gabo Island.

- Of the 43 crew on board, 38 died in the sinking.

- I-27 was part of Japan’s ‘Operation A’ submarine offensive that also struck shops off NSW and shelled Sydney Harbour (late May 1942).

- The sinking was not widely publicised in Tasmania at the time due to wartime secrecy and morale considerations.

- The wreck was discovered by the CSIRO’s RV Investigator in April 2019.

- It lies upright and largely intact in about 700m of water, 100km south of Gabo Island.

- The finding was confirmed by sonar and submersible footage. Memorial services followed in Portland and elsewhere.

- The submarine that sank the Iron Crown, the I-27, was itself destroyed in 1944 after torpedoing a troopship near the Maldives. It went down with nearly all hands.

More from Tasmania’s Past

Further Glimpses into the Island’s Long Memory

A decade after the Iron Crown sank, Tasmanians stood together in celebration.

Another story from Hobart’s quieter corners, where history and superstition meet.

Sources and References

Allan C. Green (1878–1954), SS Iron Crown, photograph, 1942. State Library of Victoria Collection.

Australian Worker (Sydney), “Go to the Head of the Queue Teddy”, 20 September 1944, page 8.

CSIRO, “Drop Camera: Bow with Anchor Chains,” image from Iron Crown wreck survey, 2019.

CSIRO, “WWII shipwreck discovered – SS Iron Crown sunk by submarine in 1942”

Researched and Written by Tamar Valley Tales

Leave a comment