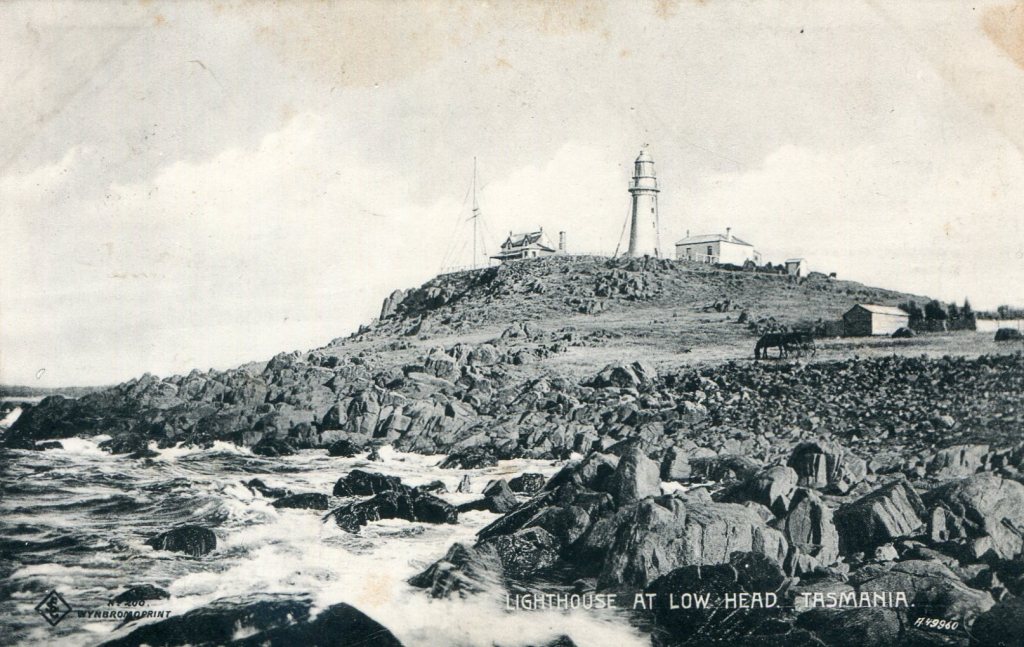

On the stormy day of June 24, 1863, the tempestuous sea off Low Head, Tasmania, roared with waves as high as mountains, crashing relentlessly against the rocky shores. The lighthouse keeper, vigilant in the face of the raging elements, saw three boats approaching the treacherous entrance to the Tamar River around 11am. Signal flags were hoisted.

Perilous Journey of the Boarding Boat

The brig named Fawn, hailing from London, signalled for a pilot to guide them into the mouth of the river for Launceston. Battling the heavy cross sea and a robust north-westerly wind, a boarding boat with head pilot, Mr Foster, and four other men struggled against the angry waves to put Foster on the boat. The boarding boat started making its way back to shore.

The boarding boat was sailing in with a lug sail. She reached Dotterel Point, just inside the lighthouse, when three colossal rolling waves hit. The boat weathered the first two, but the third pitch-poled it end-over-end, hurling the crew into the boiling waters.

Capsized and Stranded

For an agonising hour, the crew clung to the overturned vessel, battered repeatedly by unforgiving waves. As the boat drifted with the ebb tide, passing vessels, including a schooner, a brig, and the Fawn with the Senior Pilot aboard, ignored the distress signals, leaving the desperate crew abandoned.

On the shore, the men’s wives, and other women, witnessing the scene, were yelling out in despair. A rescue boat set out, manned by Robert Henry from the telegraph station, and his brother John from East Beach. Before long, they turned back. The stormy seas and adverse tide had proven too much.

The boarding boat righted itself, though still submerged beneath the rolling waves. The men shed themselves of their boots and heavier clothing and scrambled aboard. Through great exertion, the boat was brought near shore where it hit a rock, throwing the men back into the boiling sea. The strongly flowing tide carried the men closer to dry land. After a relentless struggle, three men were near enough to be reached by willing hands. They were battered and unconscious, but alive.

The fourth man, Gustavus Hardy, was seen being tossed around in the swells.

Beattie Traill’s Daring Rescue

Amid the chaos, Beattie, daughter of the assistant lighthouse keeper, was entreated by her mother to save Hardy. Beattie had grown up on the rough sea coast of Kincardine in Scotland and was known for being a strong swimmer.

Beattie tied a rope around herself and dashed into the breakers. She persevered despite being repeatedly knocked back by the waves. Swimming strongly, she reached Hardy who was being dashed against the rocks.

With difficulty, she attached the rope to Hardy and had a grim struggle with the waves to reach the shore again, with him in tow. He was alive, though bruised and senseless, after being in the water for around an hour and a half.

In the aftermath, the boarding boat was seen being dashed to pieces on the rocks.

Recognition and Gratitude

Beattie, 22 years old and a recent immigrant from Scotland, humbly played down her heroism, attributing it to the buoyancy of her crinoline. Beattie was praised for being Tasmania’s Grace Darling. Some 25 years earlier, back in England, Grace and her lighthouse keeper father had rowed a boat to rescue men from a shipwreck in wild seas.

The local community in Low Head and George Town, advocated for Beattie’s heroism to be recognised by the government. The crew of the boarding boat wrote to the local newspaper saying that Beattie “was the means of saving our lives”. The government initially demurred, questioning the legitimacy of the claims of heroism. Eventually, the government rewarded Beattie and offered a choice of £50 or 50 acres of land for “saving a life at George Town at risk of her own”. A ceremony in August 1863 celebrated her bravery, with the local community expressing gratitude through gifts and a purse.

Beattie, who later married Thomas Phillips, remained connected with Gustavus Hardy throughout their lives. Hardy, a teacher and pioneer in Scottsdale, was forever grateful to Beattie after being saved through her bravery at Low Head.

Conclusion

When a boarding boat capsized in turbulent waters, Beattie Traill, known as “Tasmania’s Grace Darling,” took swift action, tying a rope around herself and rescuing Gustavus Hardy from the treacherous sea. Her heroism earned a £50 reward, and her enduring connection with Hardy highlights the tangible impact of her bravery.

More From Tasmania’s Past

Interested in reading another story of a migrant woman in Tasmania? You may like:

Sources

A Tasmanian Heroine, Tale of Early Sixties, How a Brave Young Woman Saved Life at the Tamar Heads, Daily Telegraph, Monday 26 June 1922, p.5.

Female Heroism, Friday 10 July 1863, p. 2 The Mercury

Female Heroism, Saturday 18 July 1863, p.3, Cornwall Chronicle.

Launceston Marine Board, Cornwall Chronicle, Wednesday 19 August 1863, p.3

Ship Indiana, Launceston Examiner, Saturday 5 May 1860, p. 2

Testimonial to Mrs Ray, Cornwall Chronicle, Wednesday 12 August 1863, p.5

The People’s Hall, Launceston Examiner, Thursday 26 April 1860, p.3

Leave a comment